As a working artist, I often find myself circling back to a phrase that is repeated so frequently it begins to sound less like guidance and more like doctrine: a consistent body of work. It’s a concept emphasized in art school critiques, required for membership in many professional art organizations, and frequently cited as a prerequisite for museum and gallery acceptance. The implication is clear—if you want to be taken seriously, if you want access, legitimacy, and opportunity, your work must be immediately recognizable and neatly cohesive.

An AI-generated overview defines a consistent body of work as “a collection of works that share unifying elements like theme, style, subject matter, palette, or presentation, creating a recognizable and cohesive artistic voice that tells a deeper story and shows development over time, making it more impactful and professionally appealing.” On the surface, that sounds reasonable, even admirable. Who wouldn’t want a clear voice, a deeper story, or visible growth over time? But when I really sit with that definition and compare it to how the idea plays out in the real world, I start to feel uneasy.

In my personal experience, “consistent body of work” often translates to something far more restrictive. It frequently means that an artist has landed on a piece, a style, or an idea that has proven commercially successful or academically validated—and then continues to reproduce variations of that same work over and over again, sometimes for years or even decades, with minimal deviation. The work becomes predictable. The risk disappears. The exploration stalls.

This troubles me.

I understand the logic. If something sells, if collectors want it, if galleries respond positively, why not keep making it? From a purely practical standpoint, it makes sense. Artists need to survive. We need to pay rent, buy materials, feed our families, and maintain some level of financial stability. There is no shame in that. But I can’t help but feel that many artists build entire careers around what I would consider a stagnant artistic practice—one that prioritizes repetition over curiosity and familiarity over discovery.

Most artists I know—and I include myself firmly in that group—are energized by the act of creation itself. That excitement doesn’t usually come from doing the same thing endlessly. It comes from problem-solving, experimentation, failure, and surprise. It comes from trying a new medium, chasing a half-formed idea, or pushing a material beyond what feels comfortable or familiar. Creativity, at least for me, thrives on uncertainty.

Being shoehorned into making work that all looks essentially the same feels, frankly, boring. More than that, it feels limiting. When we commit too fully to a single visual language because it’s “working,” we risk flattening our creative lives into something safe and predictable. I think we do ourselves a disservice when we continually choose the well-worn path simply because it has already been validated, instead of testing our skills, expanding our knowledge, and allowing our practice to evolve in unexpected ways.

That said, I don’t think repetition is inherently bad. There can be value in returning to the same idea again and again—if the motivation is genuine exploration rather than obligation. Maybe the artist hasn’t quite made the piece that fully embodies the original concept. Maybe each iteration reveals something new. Maybe there is still joy, curiosity, and a deeper sense of purpose embedded in the process. In those cases, revisiting similar forms or themes can feel less like stagnation and more like refinement.

But we should also be honest with ourselves. Are we making the work because it still excites us, or because it still sells? If the answer is primarily the latter, are we truly fulfilling our intended purpose as artists? That’s not an easy question, and it doesn’t have a single correct answer. Sometimes the reality is that we need to prioritize income over experimentation. Not every season of life allows for radical creative risk. Survival matters.

For me, my creative practice is heavily shaped—sometimes constrained—by my skill set and my access to tools. I am a self-taught welder, which, as I often joke, means I am an excellent grinder. My metalwork is dictated by what I know how to do and what I physically have access to in my studio. I don’t have a forge. I don’t have expensive shaping machines. I don’t have formal training in advanced metal forming. Those limitations inevitably influence the forms I can create and the ideas I can realistically pursue.

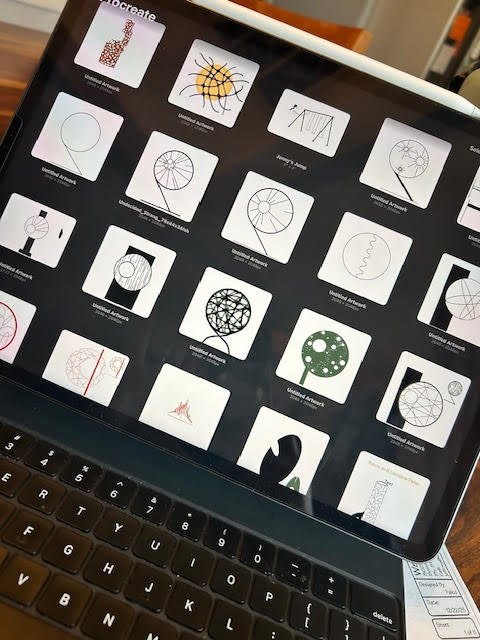

Without continued learning, those constraints could easily pigeonhole my practice. I could settle into a narrow range of techniques, repeat them endlessly, and call it consistency. But that kind of consistency feels more like complacency. Instead, I try to view my limitations as challenges rather than boundaries. Even within the tools and skills I currently have, I push myself to find new approaches, new structures, and new conceptual directions. I look for ways to use familiar processes in unfamiliar ways.

This constant negotiation between routine and experimentation raises a larger question that I don’t think has a simple answer: Is routine our enemy, or is it a necessary source of security and validation?

Routine can provide stability. It can help us build confidence, refine technique, and establish a recognizable voice. But too much routine can dull our curiosity and erode the very impulse that drew us to art in the first place. On the other hand, constant experimentation without any grounding can feel chaotic and unsustainable, especially in a professional context.

Maybe the real challenge isn’t choosing between consistency and exploration, but redefining what consistency actually means. Instead of visual sameness, perhaps consistency can live in values, in curiosity, in a commitment to growth. A body of work doesn’t have to look identical to be cohesive—it can be unified by an underlying way of thinking, a set of questions, or a willingness to take risks.

For me, that’s the balance I continue to chase. I want my work to reflect who I am now, not who I was when something first started working. I want my practice to remain alive, responsive, and open-ended. Consistency, if it means anything at all, should be a reflection of ongoing engagement—not a creative cage built from past success.